Anderson's work with his actors there arises from his response to the film's very subject. In "The Master," Anderson created sharp and confrontational images that provoked intense reactions from Phoenix and lent those reactions a powerful physicality. The character coasts on the bleary charm of the actor's line readings and the slouch of his garb: his sideburns seem to be doing most of the work. Anderson seems happy to let Phoenix merely signify Phoenix-hood and doesn't nudge him to be Phoenix.

(There are a very few exceptions-a few glorious seconds of physical comedy dispersed throughout the film).

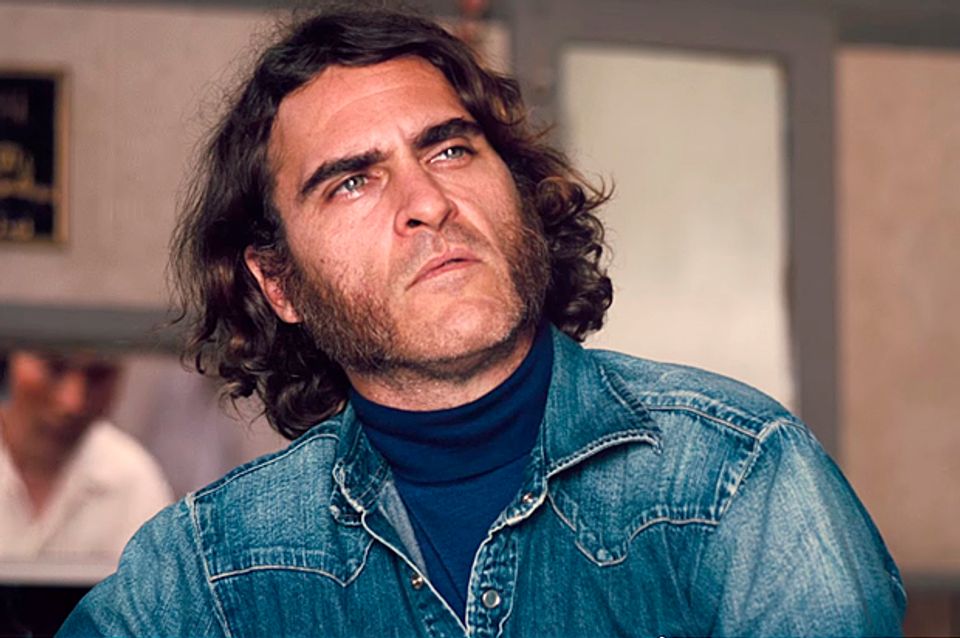

Joaquin Phoenix is one of the best living actors, but as Doc Sportello, he's coasting-digging deep neither into the emotional life of the character he's playing nor, apparently, into his own, and not subjecting his performance to the pressure of a precise and demanding gesture-repertory. They are respectful displays of performance-of the demonstrative theatrical antics into which Anderson lets his performers lapse. They're pictures, not images displays, not shots illustrations, not compositions. Anderson maps the book onto the screen by way of a cinematic approximation that seems to bypass the camera: His images lack tone they're neither fluid and graceful nor taut and intense, nor do they strike an ambiguous in-between note. His adaptation is neither a free-spirited reworking of Pynchon’s novel nor an obsessively dependent replication of it.

In the process, Doc-working through his cannabis haze-uncovers a network of intertwining conspiracies involving the police, neo-Nazis, gangsters, drug dealers, dentists, rehab facilities, rock, protest, the Federal government, and the old-line New England establishment.Īnderson's reverence for the book confines the movie between its covers. The movie, set in 1970, stars Joaquin Phoenix as Doc Sportello, a private eye in Gordita Beach, California, whose ex-girlfriend, Shasta Fay Hepworth (Katherine Waterston), coaxes him to investigate the disappearance of the wealthy real-estate developer whom she had left for Doc. Rarely has a film trumpeted its subtexts so blatantly: Anderson anoints himself as Altman's spiritual heir he’s intensely nostalgic for Altman's late-sixties/early-seventies heyday and in filming a drama set at that time, he’s going to blow the lid off the stew of conspiracies corrupting seventies America and the sixties' utopian dreams. Paul Thomas Anderson's adaptation of "Inherent Vice" bears the burden of his manifest devotion to Thomas Pynchon, but it's second to his apparent devotion to Robert Altman.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)